Emerging trends in not-for-profit fraud

The United States is host to 1.1 million not-for-profit organizations. These organizations, many of which do not maintain strong internal control processes, are ripe for fraud and embezzlement. The Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE) estimates that not-for-profit organizations sustain annual fraud-related losses of $77 billion. The aim of this paper is to answer the following questions:

- Why are not-for-profit organizations (NFPs) so susceptible to fraud?

- What are some emerging trends in NFP fraud?

- What steps can NFP directors and administrators take to protect themselves from fraud?

NFP fraud susceptibility

NFPs are particularly vulnerable to fraud. These organizations tend to place executive control in their founder, executive director, or substantial contributor. Since they often focus their funding on their core service, they tend to overlook crucial areas like accounting, internal controls, and financial oversight – functions that are of vital importance when one individual wields outsize influence on an organization.

Further, NFPs often engage volunteers, who tend to be untrained and ignorant of internal control processes, and who are privy to confidential information. Frequently, even the board of directors is comprised of volunteers with little or no financial oversight expertise.

The very nature of NFP transactions leave them susceptible to fraud as well. Transactions tend to be non-reciprocal, such as charitable contributions, which are easier to steal than other sources of revenue where consideration is exchanged. NFPs are also highly susceptible to the effects of negative publicity and therefore reluctant to report fraud when it occurs. NFPs are therefore particularly vulnerable targets for fraudsters.

Frauds commonly committed against NFPs

Some common frauds perpetrated against NFPs are as follows:

- Skimming — Cash is stolen before the funds are recorded in the accounting records

- Credit card abuse — Perpetrators either use organization-issued credit cards for personal use or use donor credit card numbers

- Fictitious vendor schemes — Perpetrators set up a company and submit fake invoices for payment

- Conflicts of interest — Board members or executives have hidden financial interests in vendors

- Payroll schemes — Continued payment to terminated employees, overstatement of hours, or fictitious expenditure reimbursement

- Sub-recipient fraud — Abuses by a sub-recipient entity include intentional charges of unallowable costs to the award, fraudulent reporting of levels of effort, and reporting inaccurate performance statistics and data

- Deceptive fundraising practices

- Misrepresentation of the extent of a charitable contribution deduction entitlement, misrepresentation of the fair market value of donated assets, and failing to comply with donor-imposed restrictions on a gift

- Fraudulent financial reporting

- Misclassifying restricted donations to mislead donors or charity watchdogs, misclassifying fundraising and administrative expenses to mislead donors regarding funds used for programs, and fraudulent statements of compliance requirements with funding sources

Fighting fraud

To effectively combat fraud and protect an NFP, leadership must establish effective internal controls. These controls must then be regularly reviewed and tested. It is also necessary to establish a fraud hotline and train staff to be equipped to deal with the occurrence of fraud.

There are a number of red flags of fraud that NFP leadership should be aware of.

- Bank reconciliations not performed in a timely manner

- One individual has control over disbursement

- Altered documents

- Inventory shortages

- Employees living beyond their means

- Accounts receivable open for long periods of time

- Donors not receiving receipts for contributions

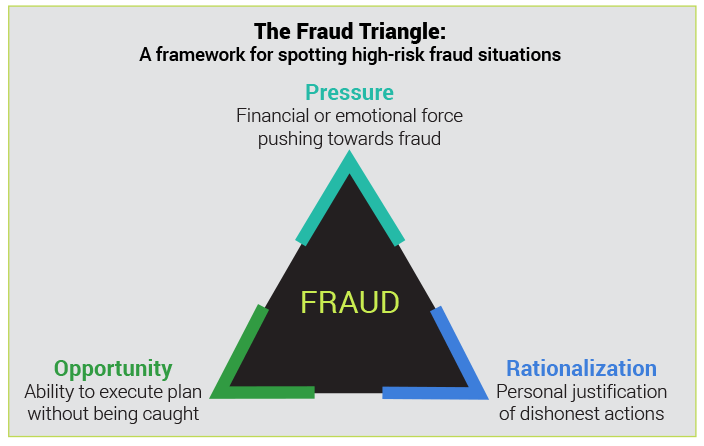

NFP leadership should also be familiar with the fraud triangle. The fraud triangle is a term coined by Steve Albrecht that refers to a framework for spotting high-fraud situations. The fraud triangle states that all fraud occurs as a result of the collusion of pressure, opportunity, and rationalization.

When formulating an anti-fraud strategy, the fraud triangle may be used in conjunction with the 10-80-10 rule of ethics. This rule is based on the assumption that 10 percent of people are ethical all of the time, 80 percent could behave unethically depending on the situation, and 10 percent are unethical all the time. The fraud triangle represents the circumstances that would result in the 80 percent of people who are not completely honest to perpetrate fraud.

Suspecting fraud

When the organizational leadership of an NFP suspects that fraud is occurring within their organization, they have a number of options. They can choose to do nothing, either to avoid the bad publicity or in the hope that the problem will disappear on its own, they can attempt to handle the issue internally, or they can engage outside investigators and/or forensic accountants to probe the issue more deeply.

The wisest course of action is the last one – to engage a team of forensic experts. These teams consist of a range of professionals such as lawyers, accountants, fraud investigators, and computer forensic specialists. These experienced financial professionals will identify how the loss occurred, preserve any available evidence, quantify the loss, control the flow of information and, in many cases, stem the loss. The forensic team will then be able to aid the board of directors in establishing adequate fraud prevention and risk management policies and take the appropriate steps to protect their organization.

Lessons learned

In combating fraud, NFP organizations must start with the tone at the top. If management behaves with integrity and meticulousness, the rest of the organization will be motivated to do the same. Management should bear in mind that most fraud is detected either through a tip or by accident and most could have been detected sooner if warning signs had not been ignored.

Moreover, the higher an individual’s position in a not-for-profit organization, the greater their ability to commit fraud. Special attention should be paid to high ranking officials. It is also important to note that not too much reliance should be placed on annual audits and that sufficient insurance coverage should be in place.

With correct preparation, internal controls, and use of experts, NFP fraud can be greatly curtailed.

For more information on this topic, or to learn how Baker Tilly tax specialists can help, contact our team.